HISTORY

100 years of social housing

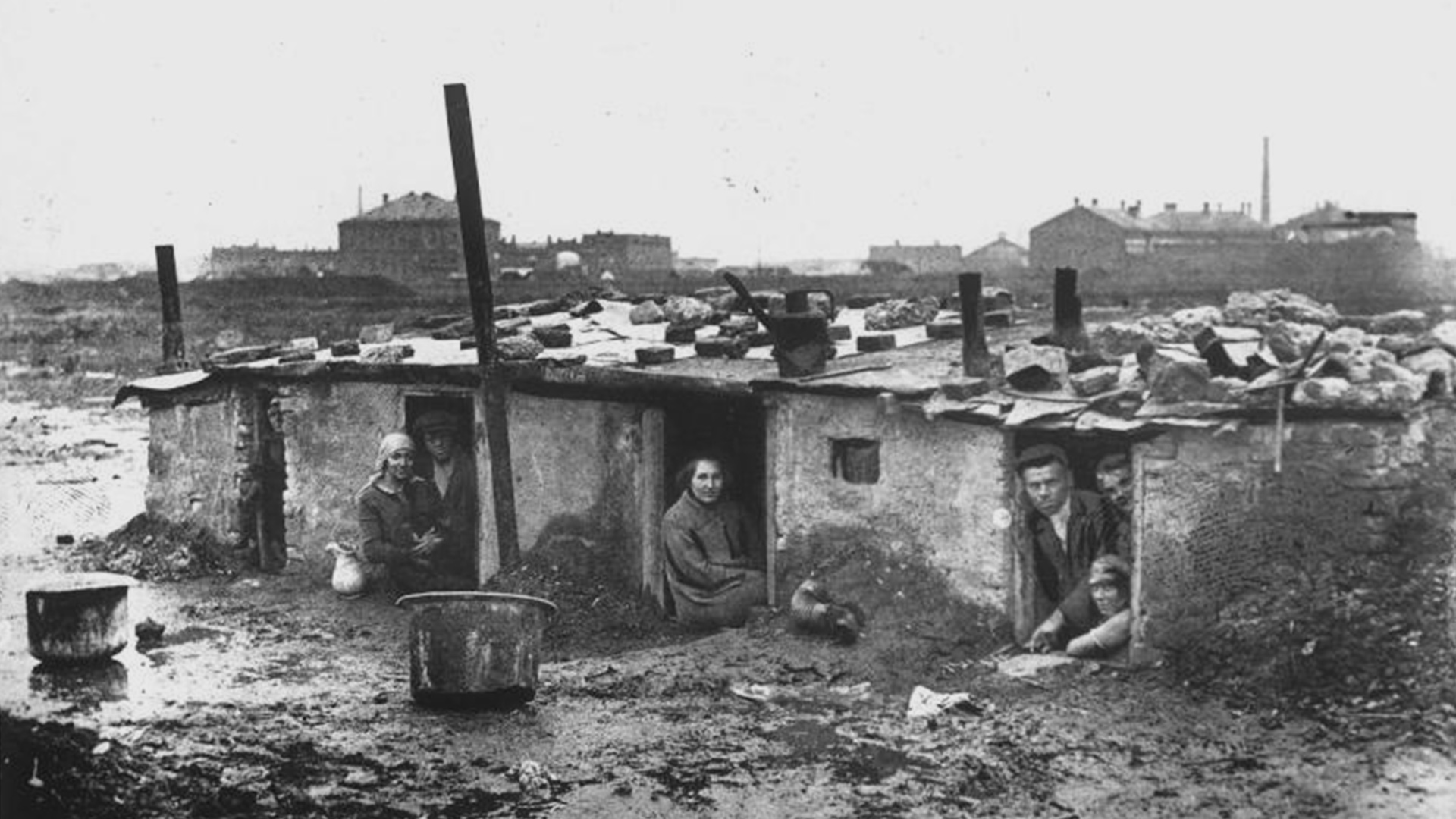

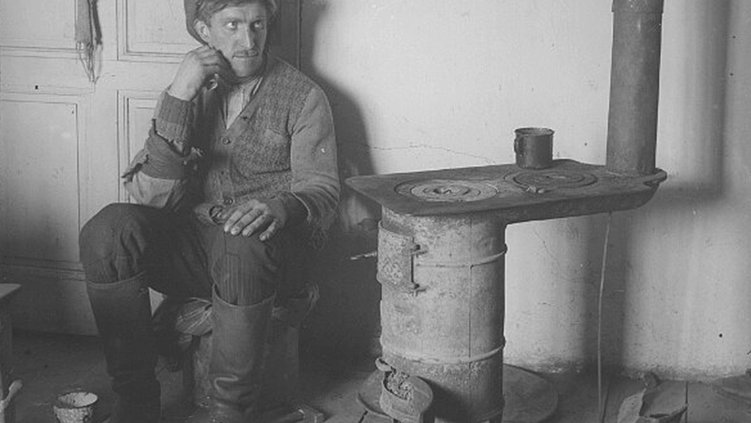

By 1918, the number of inhabitants exceeded two million. A large majority of the population lived in cramped conditions and great poverty, often in dwellings composed of just one room and a kitchen, with the kitchen only receiving light and ventilation from the corridor. There was one single water faucet (called “Bassena”) and one toilet per floor.

These dwellings were often overcrowded and additionally used by around 170,000 “bed lodgers” – who used a bed certain hours of a day, sleeping in shifts – and roomers. The extreme overcrowding and unhygienic conditions favoured the spread of tuberculosis, which was known as “the Viennese disease” and considered a typical ailment of the working class.

Despite the population decrease after the end of the First World War, Vienna’s housing shortage persisted. Building stock investments during the war years were minimal. The wives and children of conscripted soldiers were often evicted from their homes.

To ease the social climate, avoid worker unrest and protect soldiers’ families, the conservative government in 1917 issued a decree for tenant protection, which capped rents (“Friedenszins”, or “peace-rent”) and shielded tenants against arbitrary eviction. Due to the now very low rents, no roomers were taken in anymore, which made it even more difficult, above all for the lowest-income groups, to find accommodation. As a result of the hyperinflation lasting until 1922, the private construction sector came to a standstill despite the housing shortage.

After the City Council elections of 1919, Vienna’s municipal administration was taken over by the Social Democratic Workers’ Party. The subsequent turnabout of the housing sector was contingent on the fact that Vienna was given the status of a federal province of Austria, which entailed fiscal sovereignty as of 1 January 1922.

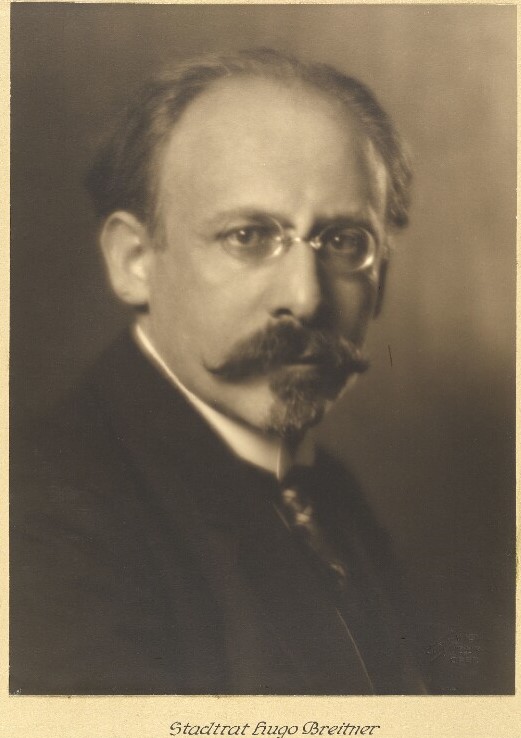

Other fundamental prerequisites for change were established by purchasing suitable building land reserves and earmarking the necessary funds for construction. A decisive impulse for social housing construction was generated by a tax reform launched by the City Councillor of Finance, Hugo Breitner. First, Breitner abolished the rent tax that had imposed the same fiscal rate on all rents and instead introduced a new tax which only affected the top 20 percent of rents. In due course, Breitner – in co-operation with Robert Danneberg – developed the earmarked housing construction tax.

Adopted in 1923, it became the most important funding base for municipal construction projects. Further revenue resulted from taxes on luxury spending of the affluent, which financed the provision of basic services for broad strata of the population while stimulating the economy.

On 21 September 1923, the City Council adopted Vienna’s first housing construction programme. The programme envisaged the construction of 25,000 flats over a five-year period. However, since the foundation stone for the 25,000th flat was laid ahead of schedule already in 1926, a second housing construction programme for another 30,000 flats was launched in 1927.

The main objective of municipal housing construction in Vienna lay in creating healthy living conditions for tenants according to the motto “fresh air, light and sunshine”. The building density of the new municipal housing projects never exceeded 50 percent.

Every unit was to offer at least one combined kitchen/living room, one bedroom, a hall and a toilet. All rooms except for the latter two were to provide direct lighting; thus, the kitchens of the past with their windows opening on a dark corridor were a thing of the past. Almost all flats disposed of private open spaces including balconies, bay windows or loggias. While water on tap was a basic amenity of every unit, most flats built in the interwar period lacked bathrooms.

87,000 dwellings were destroyed; around 35,000 persons lost the roof above their heads. The City Administration was therefore keenly interested in creating as many new dwellings as possible.

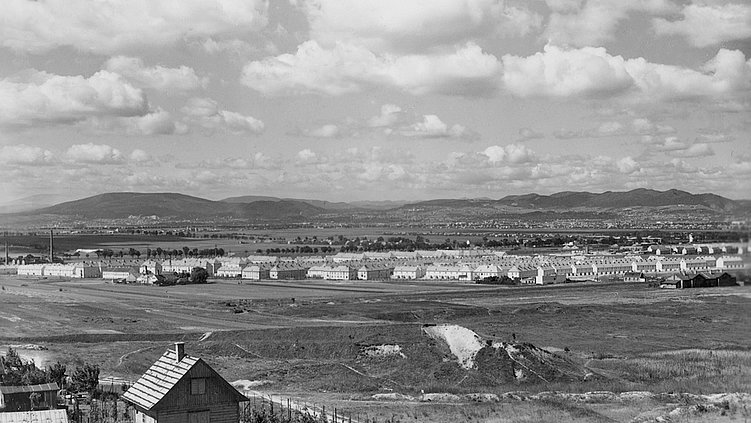

In 1947, the City of Vienna launched its first large-scale venture with the Per-Albin-Hansson-Siedlung West project comprising over 1,000 units in the 10th municipal district Favoriten. Out of gratitude for the aid extended by Sweden after the war, the complex completed in 1951 was named after the Swedish Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson.

From the end of the war until 1954, a total of 28,000 new municipal flats were built. In all, the average construction volume between 1945 and 1960 equalled close to 4,200 new municipal flats per year.

The reconstruction of Vienna was completed already before 1960, ushering in a phase of urban expansion.

In parallel with municipal housing construction by the City of Vienna, the non-municipal construction sector driven by non-profit or limited-profit building co-operatives and associations contributed significantly to post-1945 housing production overall. Between 1956 and 1965, these housing developers erected approx. 25 percent of all new dwellings in Vienna.

In 1973, the number of flats completed by limited- and non-profit housing developers for the first time exceeded that of new municipal flats. The (formerly) last completed municipal complex in Rösslergasse 15 (23rd municipal district) dated back to 2004. Due to the high demand for particularly inexpensive housing, the City of Vienna decided in 2015 to build another 4,000 municipal flats. For this reason, more than 4,000 new municipal flats are currently being constructed on city-owned plots in 13 districts.

Although many new housing policy approaches were developed and implemented over the decades, the key principles adopted by “Red Vienna” during the First Republic still hold true: affordability, high quality, social cohesion and a good social mix.

TIMELINE

Around two million persons are affected by the housing shortage, 170,000 “bed lodgers”.

Adoption of “Friedenszins” rent cap, rent control and first decree for tenant protection.

End of monarchy and proclamation of Republic of Austria.

Vienna becomes a federal province with fiscal sovereignty.

The housing construction tax (“Breitner tax”) is introduced. Vienna’s City Council decides to build 25,000 housing units.

The first municipal housing estate (Metzleinstalerhof) with 252 flats is completed.

Vienna’s City Council adopts the 2nd housing construction programme for 30,000 flats.

Completion of Sandleiten housing estate with 1,587 flats.

Completion of Karl-Marx-Hof housing estate (superblock with total façade length of 1,200 metres and 1,353 flats).

Completion of Werkbundsiedlung estate with 70 fully furnished houses created in co-operation with several artists.

Around 200,000 Viennese live in municipal flats.

Austrofascism and National Socialism bring construction activities to a standstill.

87,000 dwellings are destroyed; around 35,000 persons are homeless.

Construction of Per-Albin-Hansson-Siedlung West with 1,033 flats.

The City of Vienna adopts a rapid-relief construction programme, predominantly with small “duplex units”, which could be combined into one bigger flat at a later date.

The 100,000th municipal flat is completed.

The Housing Promotion Act enters into force.

Urban expansion: An average of 9,000 new municipal flats is built every year.

Beginning of construction works for Per-Albin-Hansson-Siedlung East with over 5,000 flats.

The 10,000th flat after the end of the Second World War is completed.

Completion of Grossfeldsiedlung development with 5,533 flats.

Completion of Am Schöpfwerk housing estate with 990 flats.

Retrofitting of the 1,000th lift in a municipal housing estate.

The 200,000th municipal flat is completed.

The new tenancy law and the Vienna housing promotion regulations enter into force.

The Vienna Land Procurement and Urban Renewal Fund is set up. Every year, around 10,000 flats are rehabilitated.

The Vienna Housing Promotion and Housing Rehabilitation Act enters into force. The Iron Curtain is dismantled, leading to mass immigration from the neighbouring countries east of Austria.

A new housing construction campaign is launched. The City of Vienna subsidises up to 10,000 new flats per year.

Amendment of tenancy law.

Both developers’ competitions and the Land Advisory Board are introduced.

Wohnservice Wien is established. The thermal rehabilitation programme “THEWOSAN” is launched.

The entire subsidised housing segment is transferred from the City of Vienna to non-profit and limited-profit housing developers. The (until then) last municipal housing estate in Rösslergasse (23rd municipal district) is completed.

The new neighbourhood service wohnpartner takes up its activities in Vienna’s municipal housing estates. The Housing Promotion Act is amended; in this way, municipal housing estates are to be made accessible to new target groups, thereby ensuring an improved social mix.

Launch of SMART housing construction programme.

The City of Vienna adopts the new construction programme “Municipal Housing NEW”; approx. 4,000 municipal flats are to be built.

Introduction of the new zoning category “Subsidised Housing“. The first project of the “Municipal Housing NEW” programme is taken over by its tenants (Barbara-Prammer-Hof).

21 municipal housing projects are in the planning or construction phase and due for completion by 2026.

Further “Municipal Housing NEW” estates are taken into operation in the Wildgarten urban expansion area (12th municipal district) and on the premises formerly occupied by the Leopoldau gasworks in Floridsdorf (21st municipal district).